The Earth in Perspective (2) - Gas Giants

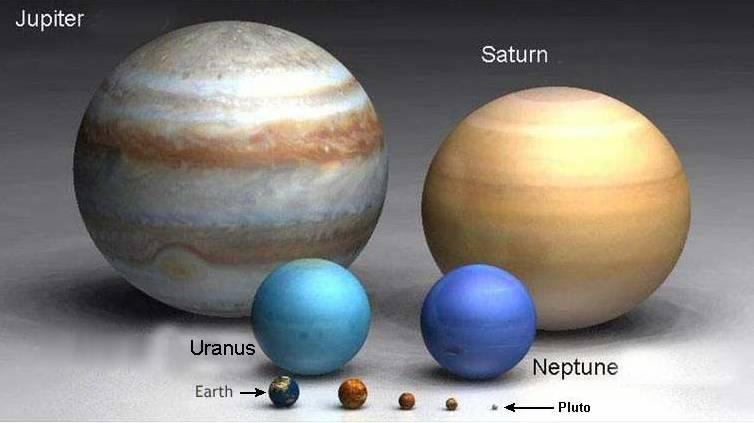

Scaled up now to include the solar system’s four gas giant planets.

Jupiter has an (equatorial) diameter of 143,000 km.

Scaled up now to include the solar system’s four gas giant planets.

Jupiter has an (equatorial) diameter of 143,000 km.

Unlike the previous image, these four planets are shown with their atmospheres, since they consist primarily of atmosphere and probably have no solid surface. So what you are looking at for Jupiter and Saturn are the cloudtops. The atmosphere is primarily hydrogen and helium, but for Jupiter and Saturn, ammonia is the main secondary constituent. If you descended beneath their clouds all you would encounter is a steadily thickening gaseous shell, eventually merging into a layer of solid hydrogen, and finally, deep inside, a rocky / metallic core (although the internal structure of these planets remains a matter of conjecture).

Being further out and smaller (and thus colder, getting less heat both from the sun and internally), Uranus and Neptune have much less active atmospheres and lack the colourful bands of clouds that characterise Jupiter and Saturn. They are sometimes called 'ice giants'; the dominant secondary component of their atmospheres is methane. Wisps of bright, high cloud do occasionally appear, particularly on Neptune (although slightly smaller than Uranus, Neptune is slightly more massive, and thus although Neptune is further from the Sun, Uranus is colder).

The distinctive rings of Saturn aren’t shown here. All four of the giant planets have some sort of ring system, but that of Saturn is the most extensive and visible. They also each have a large family of moons circling them. Two of these, Jupiter’s moon Ganymede (equatorial diameter 5,262 km) and Saturn’s moon Titan (equatorial diameter 5,152 km), are larger than Mercury in size, though both are much less massive than Mercury.